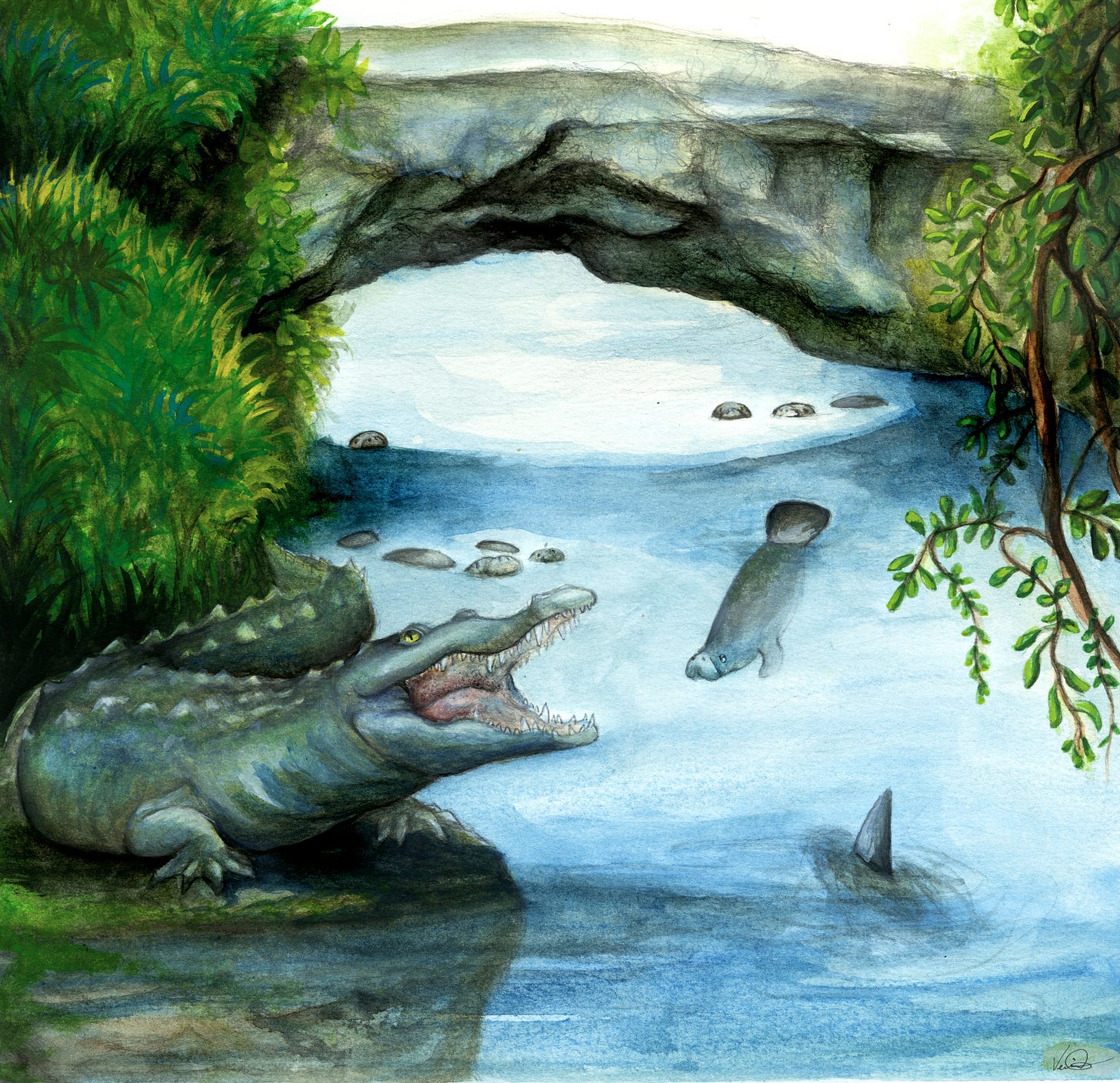

Gladiator and the Crocodiles of North Miami's Arch Creek

Originally published in the third print issue of Islandia Journal, here's Eric King's story of Gladiator, a crocodile who was raised by manatees at the historic Arch Creek.

There’s a small, 9.8-acre park in North Miami that is sandwiched between the FEC railway tracks and US 1, called Arch Creek. This dense corner of tropical hardwood hammock, otherwise overlooked, or mistaken for “the one with the ponies,” is where thousands of years of human activity intersected on the rocky terrain of a natural limestone foot bridge. The military trail of the 3rd Seminole war, the first tax-payer funded road in 1892, and eventually the controversially-named, Dixie Highway in 1912, all followed paths over the natural limestone bridge. The creek that ran beneath was described as having the “cleanest deep waters, full of the finest fish.”1 It was also where a legendary crocodile named Gladiator once made his home at the turn of the 19th century.

In the mid to late 1800s, reports began to emerge of fearless, if not foolish, humans engaging in vicious battles with crocodiles at Arch Creek. Most of these entanglements were done so in the name of science: First in 1874, when a 14’2” behemoth named Old Crock was captured and stuffed by a local taxidermist named William Hornaday. Hornaday declared that Old Crock was the first true crocodile ever captured on American soil. Common sense challenges that claim. Even the Commodore, Ralph Munroe of Coconut Grove fame, rose to the challenge of killing a crocodile at Arch Creek. Along with Charles Peacock, the two fought and vanquished a 14’8” croc, later donating it to the American Museum of Natural History where it was displayed in 1887.

In slight contrast to these stories where brave men conquer beast, proclaiming victory with masculine roar... we have Gladiator, the Crocodile of Arch Creek. In 1898, a doctor by the name of John G. Dupuis moved to Lemon City (present-day Little Haiti) and established his medical practice in what is now a historically-designated building that still stands along NE 2nd Avenue2. That same year he founded White Belt Dairy, believing fresh milk was a necessity for good health. When the Yellow Fever epidemic hit Miami in 1899, Dupuis was said to be one of the few white doctors trusted by the Seminole Tribe. They, in particular a Seminole named Alligator Joe, shared the story of Gladiator with Dupuis, who then printed the account in a privately-published document called History of Early Medicine, History of Early Public Schools, History of Early Agricultural Relations in Dade County, in 1954.

According to Dupuis, Gladiator originally lived in Indian River with his equally crocodilian, but much larger parents. When he was a baby, Gladiator was uprooted from his home and blown into the waters of Arch Creek during a severe, but unspecified hurricane. Almost immediately, the young crocodile was taken under the flipper of a maternal manatee who protected Gladiator and taught him gentle, meandering ways of the Sea Cow3. Despite this, Gladiator was still a crocodile. As he grew larger, Gladiator became a fierce advocate and protector of his home and surrogate family. Sharks, saw fish, and other invaders all met their demise “without fear or favor” if they came within proximity. Manatees, on the other hand, were always left alone if they entered Arch Creek.

It is not known how long Gladiator had resided in the waters of Arch Creek, or even if his story, as told by Dupuis, is entirely factual. By the early 1900s, Arch Creek and the natural limestone bridge were fast becoming a popular tourist spot where community barbecues and political rallies were often held, sometimes with Dr. Dupuis in attendance. Without their current protections, even a crocodile with as flowery a story as Gladiator, could be seen as a threat.4

And so, Gladiator, like the crocodiles of Arch Creek before him, met his demise via a rifle’s bullet. While it has never been explicitly stated that Dupuis himself pulled the trigger, for more than 50 years the sprawled, plated skin of a massive crocodile hung in the lobby of the White Belt Dairy farm, greeting all who visited.

Unfortunately, Arch Creek no longer boasts clear waters and the natural limestone bridge collapsed under mysterious circumstances in 1973. A replica of the bridge was built in 1988 with the help of warlock and renowned tiki artist, Lewis Vandercar.

EDITOR’S NOTE. At the time of this essay’s original publication, the building was still standing. On January 24th, 2024, the historically protected Lemon City Drugstore was demolished “by neglect” when its owners, the developers of Miami’s so-called Innovation District allowed it to decay into irreparable condition.

This writer believes that the manatee who took Gladiator in deserves high accolades and possibly as cool a name as her surrogate offspring.

If Gladiator were to live in Arch Creek today - it has been decades since a crocodile has been seen there - he would be left alone as crocodiles are now protected under the Federal Endangered Species Act. It is not uncommon to encounter crocodiles in South Florida, though. Greynolds Park, for instance was graced for years with a 10-11 foot croc that could be seen in one the park’s lakes, if you knew where to look. FWC-sponsored pamphlets titled Living with Crocodiles were handed out to those who would complain about it. Crocodiles are known to travel up and down the Oleta River and have even wound up on the back porches of residences along the river. Of course, if you want to see crocs outside of urbanized areas, Flamingo in the Everglades is an ideal spot.

Works Cited:

THE GREATER NORTH MIAMI HISTORIAN Winter Edition Volume III Number IV (January 2001) - “GLADIATOR” THE SAVAGE CROCODILE OF ARCH CREEK pg 1

DUPUIS MEDICAL OFFICE AND DRUGSTORE 26041-45 N.E. 2 AVENUE Historic Designation Report (1985)

Tequesta #XLVII (1987) - Arch Creek: Prehistory to Public Park pgs 8, 9

Thanks for sharing, Islandia. Glad you made the note about the Dupuis building being torn down this year.

I recall Lewis Vandercar coming down from his home near Tampa to work on the fallen Arch, which he reconstructed. That area was a popular Lover's Lane in the 1960's, and the hardwood hammock was magnificent. I had met Vandercar at his home off Biscayne Boulevard, near Sears, back in 1965. I visited his yard with my girlfriend, who he promptly asked if she would pose nude so that he could paint her portrait. She declined. His yard was filled with terrific concrete statues of very weird creature and people.